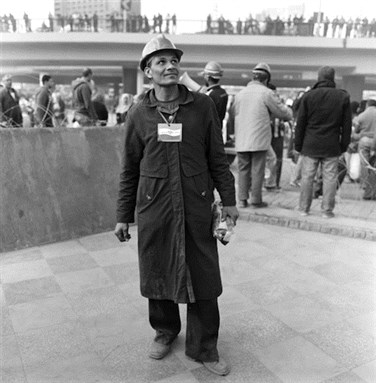

One of the most wrenching images from the November 2012 conflict between Israel and Hamas was that of BBC journalist Jihad Masharawi holding the shrouded body of his eleven-month-old son. His face is gripped with agony, his eyes closed as he looks upward. We can imagine that he feels utterly alone in his grief, but he must also be aware of the men around him in this hospital room. Some or all of the men are likely fathers, uncles, or older brothers to young children. They reach out to touch Masharawi on his shoulder. In their downcast glances, I feel I recognize the strange shame of people who wish they could do more. Behind the camera, taking the picture, is a colleague, Majed Hamdan, a photographer for the Associated Press. Behind the photographer are all of us.

The photograph was on the front page of the The Washington Post on 15 November, and apparently it caused a hassle for the paper. According to ombudsman Patrick Pexton, many accused its placement of being biased. Many asked why this image was not “balanced” with one of Israeli suffering. Pexton replied that no such image existed, since, as of the day of Masharawi’s son’s death, no Israeli civilians had been killed by Gaza rocket fire for over a year. Pexton also described the fundamental imbalance in arms between Israel and Hamas, and concluded, “Let’s be clear: The overwhelming majority of rockets fired from Gaza are like bee stings on the Israeli bear’s behind.”

He is suggesting, but does not say outright, that an expectation of balance is unreasonable not only because an equivalent image from the “other side” may not be available but for another reason as well. Expecting balance obfuscates our understanding of conflicts that are not in reality balanced. Israel has some of the most advanced military technology in the world. Hamas has rockets with limited range and accuracy. Even more fundamentally, Israel remains the occupying power over Gaza, and thus has ultimate responsibility for civilian welfare—as well as a legal responsibility to end the occupation. (The metaphor of balance and the seesaw image it evokes has other problems, too. The myth of “two sides” to the conflict obscures differences of opinion and hierarchies of power within Israeli and Palestinian societies.)

If balance is not a good guiding value when producing news about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, then how else can we evaluate the newsworthiness of this image? For Paxton, the strength of the photograph is in its universality. He writes, “That the man is Palestinian—not a terrorist but a journalist—and that the bomb was dropped by Israelis, to my mind is almost beside the point. This photo depicted loss and pain, the horrific cost to innocents on both sides of the violence in the Middle East.”

This universalizing quality is an important value, but the strength of an image also lies in the way in which it can speak to multiple audiences at once. Many Americans will look at this picture in the universal way that Paxton does and see a father, any father. Perhaps they will experience a moment of surprise when they realize that this man is Palestinian—and a BBC journalist at that. Some audiences need no schooling on Palestinians’ flesh-and-blood, heart-and-soul humanity, but for a broader public photographs such as this one are an important reminder of the insecurity faced by most Palestinians as they try to care for loved ones. But for those who follow the Israeli-Palestinian conflict closely, this image carries a slightly different meaning since it falls into a whole series that shows Palestinian parents’ inability to protect their children in the face of large-scale Israeli violence. There is the image of Muhammad Al-Durrah, killed by Israeli gunfire, being cradled by his father. There is also Huda Ghalia weeping on the beach in Gaza near the body of her father and five of her siblings. There are others. And now we have this image.

Whether one sees it as an image of universal suffering as a result of war or as a particularly Palestinian image, photographs like this summon honest introspection and difficult feelings, perhaps even more than the bloody images of conflict that often cause viewers to avert their eyes. Given news standards that lead journalists all too often to focus on leaders’ statements and casualty statistics, it is a small moral breakthrough that this image should take up space on the front page of a major paper. It is an invitation to feel something about a Palestinian family far removed from Washington, DC.

Yet, photographs like this one have provoked the argument that dead children are part of Hamas’ media strategy. According to this argument, Hamas baits Israel into killing Palestinian children in order to make Israel look bad. On 18 November, 2012, a post on HonestReporting concluded, “The media must acknowledge that dead babies and children play an essential role in Hamas’ propaganda war.” A few days later, in a blog entry entitled “The Media Bear Some Responsibility for Civilian Deaths in Gaza,” law professor Alan Dershowitz took the argument a step further by asserting that the media are complicit in the deaths of Palestinian children: “If the international community and the media want the conflict between Hamas and Israel to end, they (OR: we) must stop encouraging this gruesome Hamas tactic.”

On 28 November, 2012 in The Washington Post’s op-ed pages, the Israeli ambassador to the United States, Michael Oren, picked up the argument. Oren asserted that Hamas has a strategy of making it seem as though Israel is perpetrating war crimes, and that the US media “help advance its strategy.” “Hamas knows,” he writes, “that it cannot destroy us militarily but believes that it might do so through the media.” In other words, while Israeli missiles killed an estimated 103 civilians—including three journalists and 33 children—and Hamas rockets killed four Israeli civilians during the November fighting, and even though Israel has been carrying out a crippling economic blockade against Gaza for five years, it is Hamas that poses the existential threat to the state of Israel via its media strategy.

Because I have been researching this topic, I know that this is not the first time such an argument has been made. It is, of course, impossible for a photograph of a dead child, or even many photographs of many dead children, to destroy the state of Israel. Israel’s public image certainly influences its economy, military strategies, and negotiating position, but a direct cause and effect argument is extremely weak. This is not the only problem with the argument. The claim that Hamas intends to have Palestinian children killed for the sake of international media is unsubstantiated, to say the very least. The contention that the media are complicit with Hamas or even with a broader Palestinian perspective is also, of course, rather tendentious. But what bothers me the most right now is that given the amount of blood being shed, it is disingenuous of the Israeli ambassador to equate potential damage to Israel’s image with the loss of lives and homes that the phrase “existential threat” evokes. Given that Israeli missiles endangered and killed journalists last month, it is especially distasteful for him to blame journalists.

It is hard enough to learn about the world and care about people we have never met without having to read op-eds by officials that try the limits of logic. So I must return from that cliff of disdain to the concrete losses: that of Jihad Masharawi, and all of the other Palestinian and Israeli mothers and fathers and sisters and brothers and friends who have lost loved ones in this conflict, lost to missiles and bullets and rockets and bombs and jail cells, as the Israeli government continues to perpetuate its control over another people.

![[Front page of the 15 November edition of the Washington Post newspaper featuring Majed Hamdan`s photo of Jihad Masharawi mourning his son`s death.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/WaPo_MasharawiMourns.jpg)